|

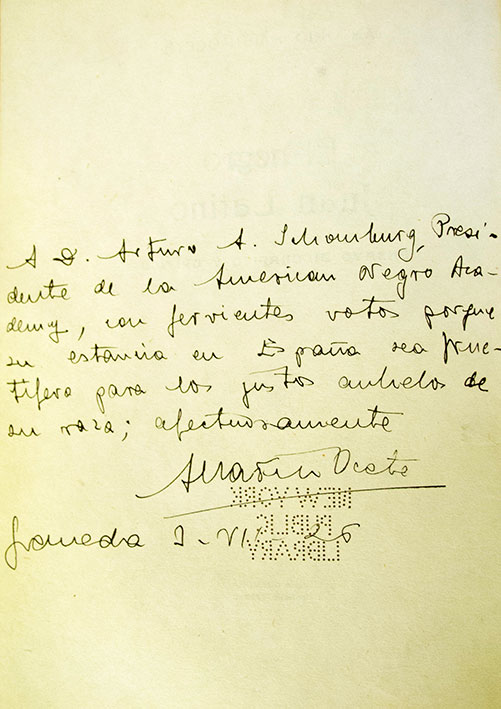

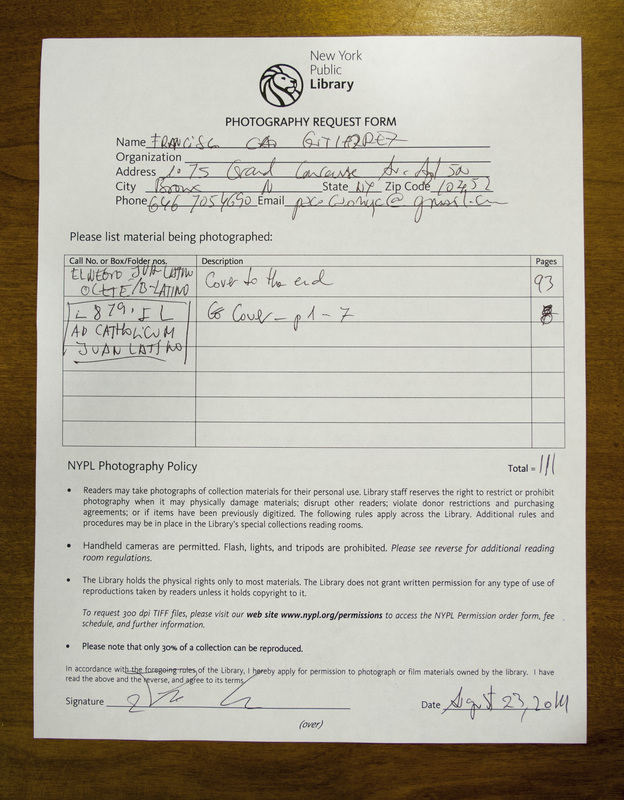

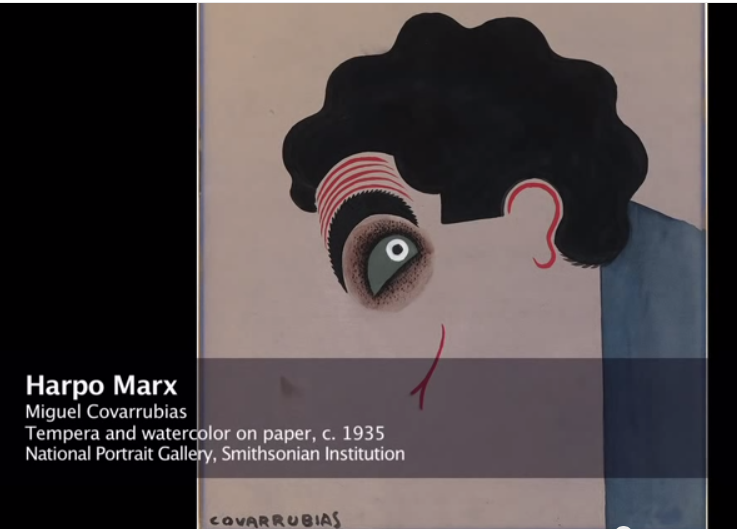

The historical aspects of this project are based on research carried out at New York Public Library-Schomburg Center for Research in Harlem. After receiving an Smithsonian Award, the research expanded to the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C.

The fictional elements of the story are comprised of works created specifically for the project, using different formats: written text, photographs, paintings, manuscripts, printed materials books, and illustrations. Those works will be based in disciplines such as music, theater and dance. The project aims to combine the techniques of a historical novel with museum curatorial practice. |

|

HISTORICAL FACTS: BIBLIOGRAPHY

HISTORICAL FACTS: ARTHISTORICAL FACTS: MUSIC

HISTORICAL FACTS: DANCE

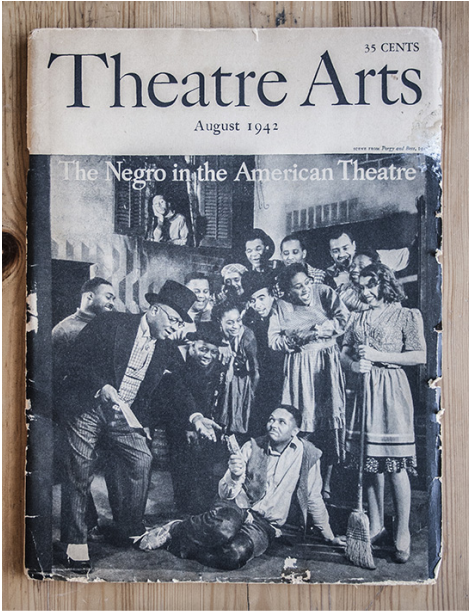

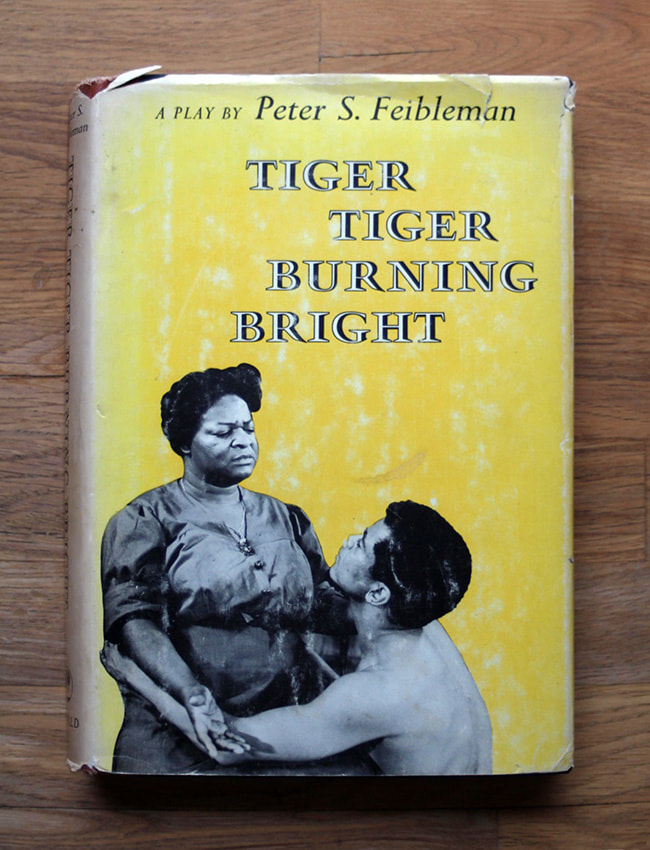

HISTORICAL FACTS: THEATER

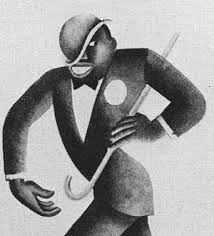

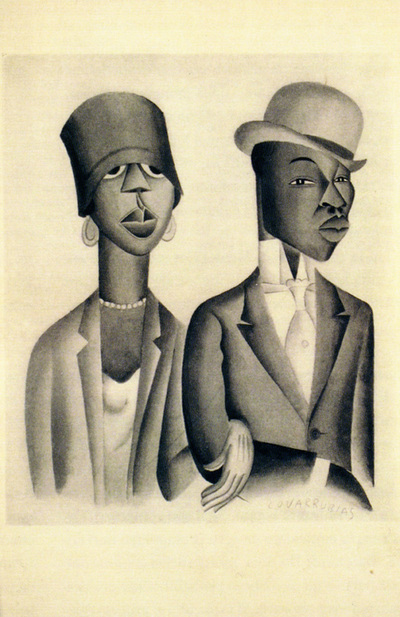

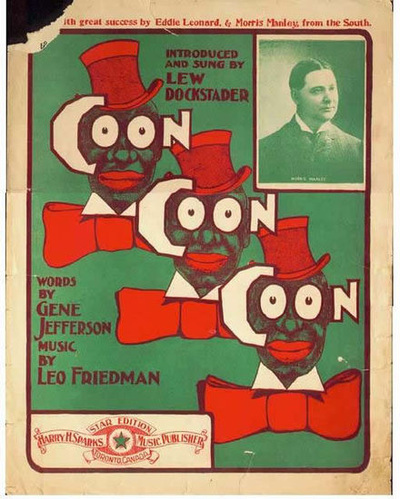

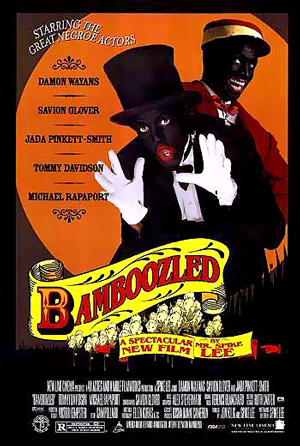

Blackface is a form of theatrical makeup used by performers to represent a black person. The practice gained popularity during the 19th century and contributed to the proliferation of stereotypes such as the "happy-go-lucky darky on the plantation" or the "dandified coon".[1] In 1848, blackface minstrel shows were an American national art of the time, translating formal art such as opera into popular terms for a general audience.[2] Early in the 20th century, blackface branched off from the minstrel show and became a form in its own right, until it ended in the United States with the U.S. Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.[3]

Stereotypes embodied in the stock characters of blackface minstrels not only played a significant role in cementing and proliferating racist images, attitudes, and perceptions worldwide, but also in popularizing black culture.[6] In some quarters, the caricatures that were the legacy of blackface persist to the present day and are a cause of ongoing controversy. Another view is that "blackface is a form of cross-dressing in which one puts on the insignias of a sex, class, or race that stands in binary opposition to one's own."[7] By the mid-20th century, changing attitudes about race and racism effectively ended the prominence of blackface makeup used in performance in the U.S. and elsewhere. It remains in relatively limited use as a theatrical device and is more commonly used today as social commentary or satire. Perhaps the most enduring effect of blackface is the precedent it established in the introduction of African-American culture to an international audience, albeit through a distorted lens.[8][9] Blackface's groundbreaking appropriation,[8][9][10] exploitation, and assimilation[8] of African-American culture—as well as the inter-ethnic artistic collaborations that stemmed from it—were but a prologue to the lucrative packaging, marketing, and dissemination of African-American cultural expression and its myriad derivative forms in today's world popular culture.[9][11][12] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackface FILMS

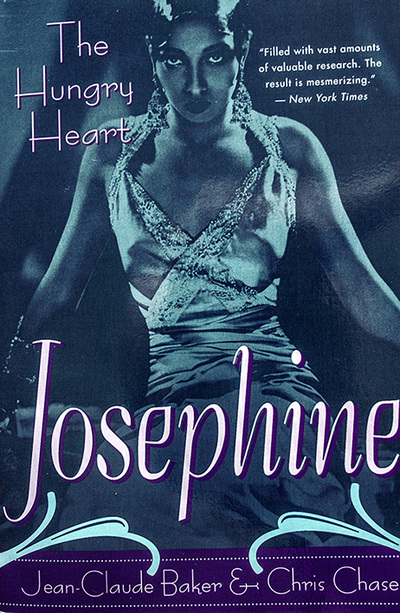

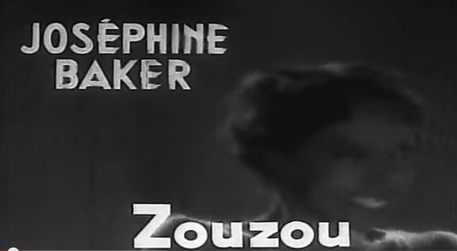

Zouzou (1934) - Josephine Baker Film (in French)

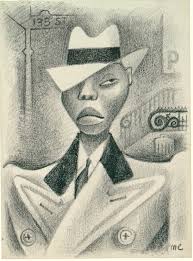

As children, Zouzou (Josephine Baker) and Jean are paired in a traveling circus as twins: she's dark, he's light. After they've grown, he treats her as if she were his sister, but she's in love with him. In Paris, he's a music hall electrician, she's a laundress who delivers clean underwear to the hall. She introduces him to Claire, her friend at work, and the couple fall in love. Jean conspires to get the show's star out of town and for the theater manager to see the high-spirited Zouzou perform. When Jean's accused of murder and Zouzou needs money to mount his defense, she pleads to go on stage. Her talents may save the show, but can anything save her dream of life with Jean? (Summary from Wikipedia) Cast (IMDB): Josephine Baker as Zouzou (as Joséphine Baker); Jean Gabin as Jean; Pierre Larquey as Papa Melé; Yvette Lebon as Claire; Illa Meery as Miss Barbara; Palau as Saint-Lévy; Madeleine Guitty as Josette; Claire Gérard as Mme. Vallée; Marcel Vallée as M. Trompe; Roger Blin as (uncredited); Geo Forster as (uncredited); Serge Grave as Young Jean (uncredited); Teddy Michaud as Julot (uncredited); Philippe Richard (uncredited); Viviane Romance (uncredited); Robert Seller (uncredited); Adrienne Trenkel (uncredited); Lucien Walter (uncredited); Andrée Wendler (uncredited). 1927- The Jazz Singer The notorious blackface conclusion to the first "talkie," the Jazz Singer. In the effort to accept blame for producing the film but avoid negative backlash of its overt racism, the studio who owns the intellectual property has allowed the visual but disabled the audio. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UYOY8dkhTpU Excerpt from Miguel Covarrubias' "La Isla de Bali" (filmed in the 1930s) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W9DScGxfabU ACQUISITIONS

|

|

HISTORICAL FACTS: CHARACTERS

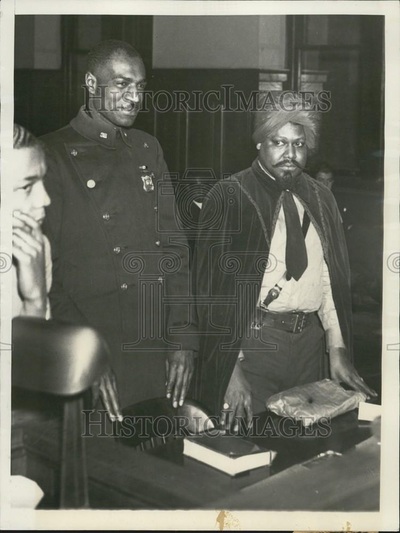

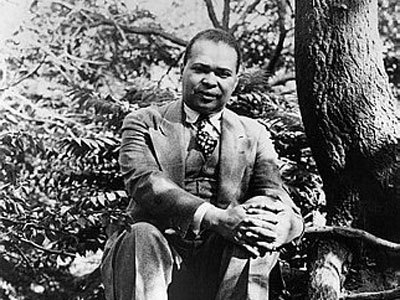

Charles Gilpin was an actor, vaudeville performer and singer who received high praise for his portrayal of Brutus Jones in Eugene O'Neil's The Emperor Jones in 1920. With that, he became the most well known black stage actor to play in a lead role. In 1921, he was named one of the 10 best artists who had made a valuable contribution to the American Theater, the first black actor ever to be so honored.

Image Credit: John D. Kisch/Separate Cinema Archive/Getty Images

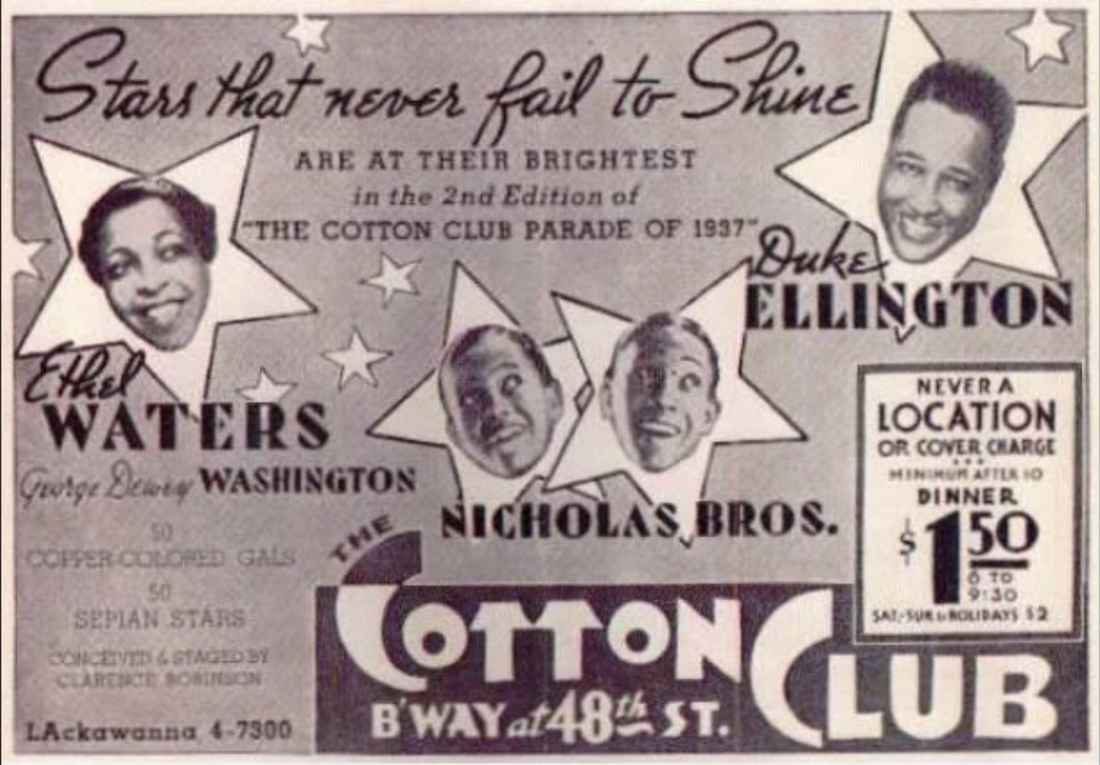

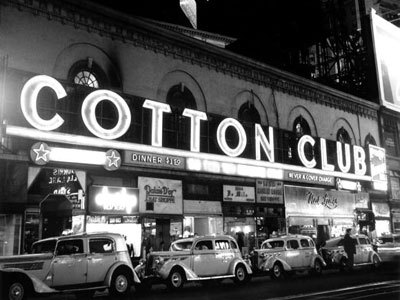

Duke Ellington's band was the house band at the Cotton Club for four years, starting in 1927. The band leader, pianist and prolific composer (with more than 1,000 compositions to his credit) brought jazz into the limelight, no doubt thanks to his charisma.

Image Credit: Getty Images

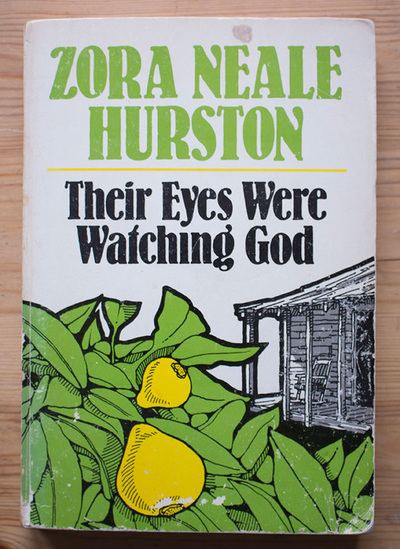

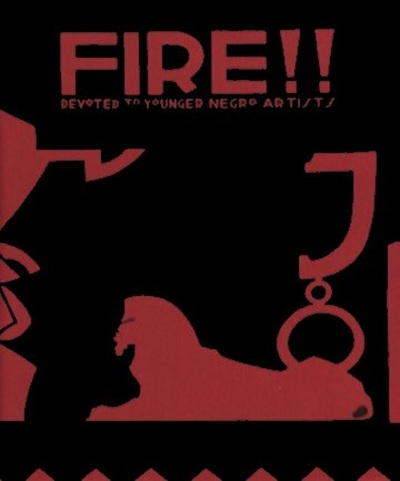

Zora Neale Hurston was another key writer of the period, helping shape the culture during the Harlem Renaissance with her fiction, poetry and essays. She helped publish, along with Langston Hughes and others, a literary magazine called Fire!! that promoted the work of the writers and artists who were causing a stir during the Renaissance. Her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) is her most well known work. Hurston had received a Guggenheim fellowship to do ethnographic research in places such as Jamaica and Haiti. Their Eyes Were Watching God was the novel that grew out of her time performing that fieldwork.

Image Credit: Getty Images

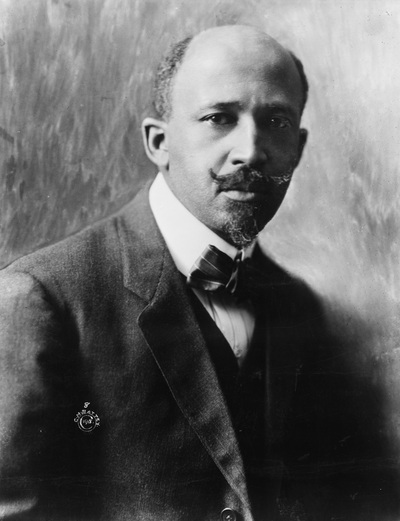

Augusta Savage was a sculptor who, in the early 1920s, attended the Cooper Union art school, where she sold a sculpture of W.E.B Du Bois that was placed in a branch of her work of the New York Public Library. She received other commissions for her work, and continued to exhibit new pieces through the decade, culminating with her well known.

Image Credit: Getty Images

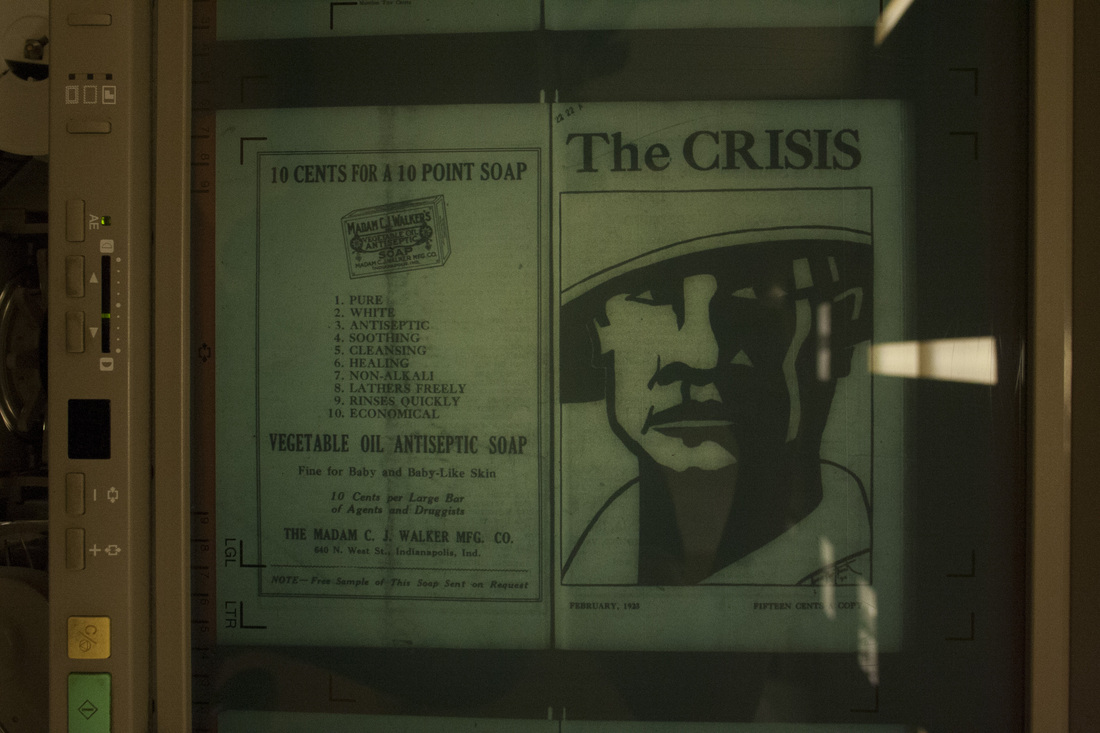

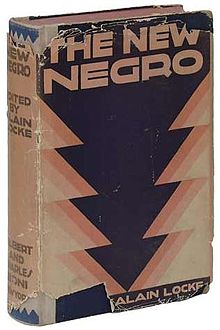

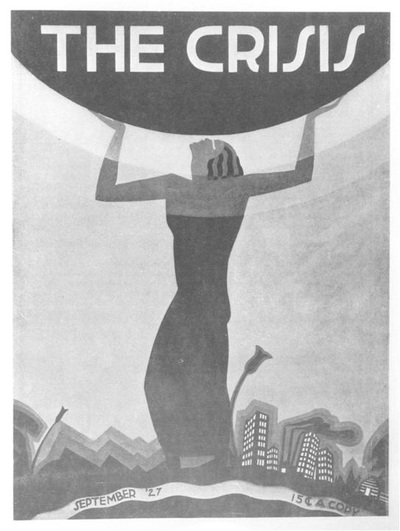

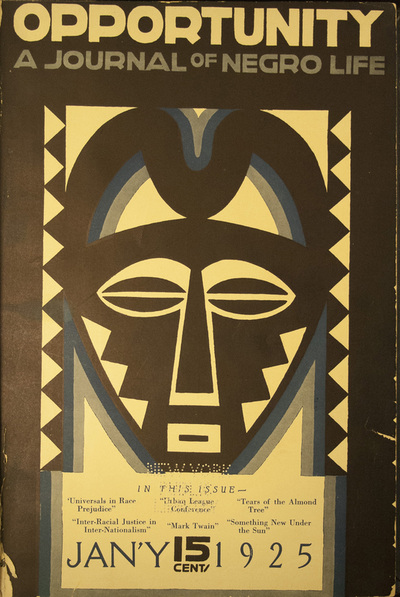

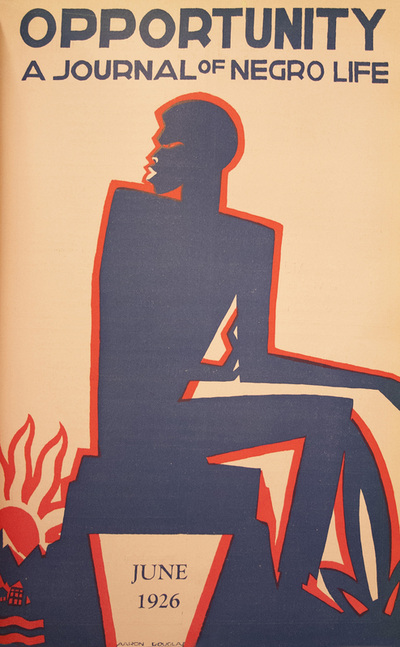

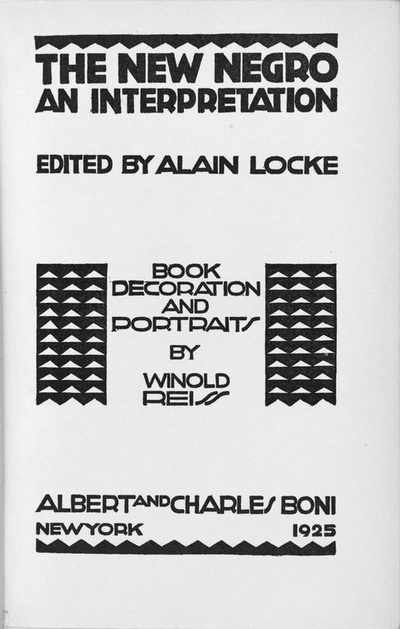

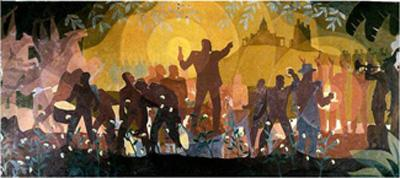

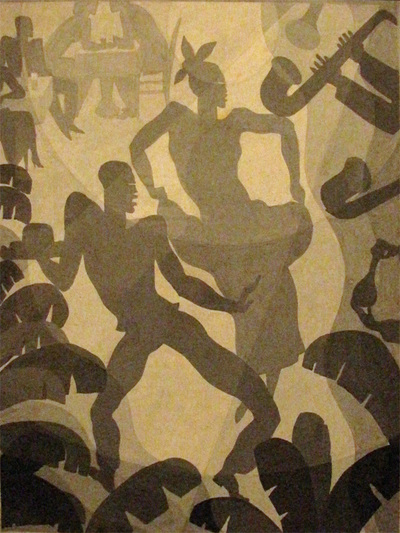

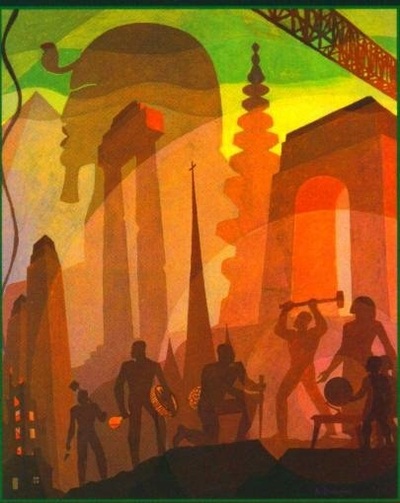

Painter Aaron Douglas was a force during the Harlem Renaissance. He did illustrations for key magazines of the era such as The Crisis and Opportunity, and in time developed a modernist style he would apply to African subject matter. His work was considered unique among African-American artists. Writer Alain Locke called Douglas a "pioneering Africanist" and used the artist's illustrations in his anthology The New Negro (1925).

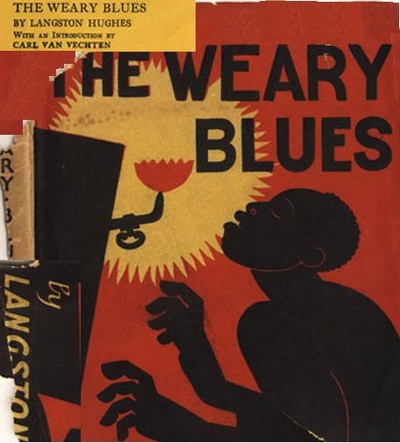

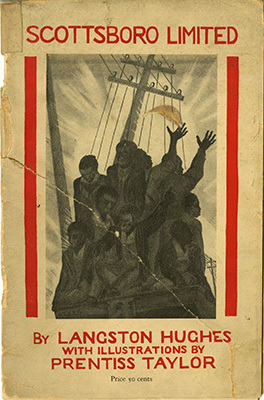

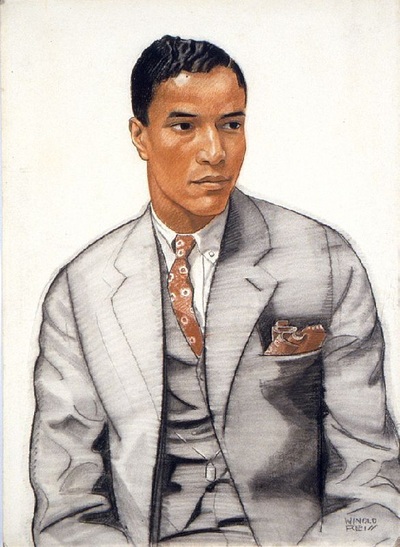

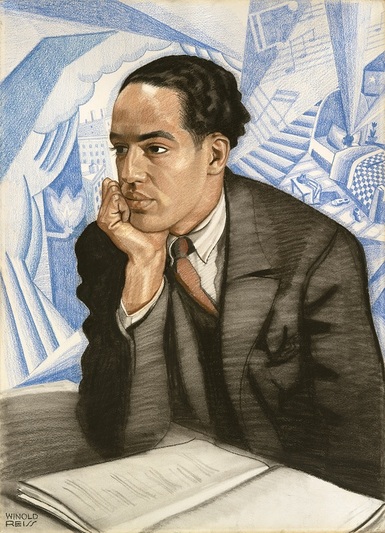

Image Credit: Getty Images Langston Hughes wrote about black life in America in his novels, plays, poetry and short stories. His work during the 1920s was very influential in artistic circles during the Harlem Renaissance, and his poetry celebrated the influence of jazz on his writing. He lived in Harlem for most of his life.

Portrait by Winold Reiss. Image Credit: National Portrait Gallery, Washington D.C.

|